Biographical Essay by Nicholas Williams (1998)

Biographical Essay by Nicholas Williams (1998)

A number of far-sighted twentieth-century composers have tried to reconcile aspects of Indian culture with Western music. It is only in the last two or three decades, however, that the work of composers who themselves hail from the Indian Sub-continent have been heard in European concert halls. Within this corpus of distinguished creative achievement, the music of Delhi-born Param Vir holds a unique place. The product of a sensitive, exacting mind, it is finely wrought and sparingly yielded to the world. Following no party line and conforming neither to putative notions of Indian music or current ideals of complexity or multiplicity, it has earned the particular respect of audiences and performers both in the realm of contemporary music and beyond.

It is a respect that stems from Vir’s regard for the integrity and humanity of his audience, and from the demands that he has required of himself. Though already a composer of music-theatre when he first visited the Dartington Summer School in 1983, he set out from that point in time to master the language of musical modernism without taking easy options. A philosopher who trained at Delhi University, Vir brought intelligence and dedication to a concentrated apprenticeship that was swiftly rewarded with impressive results. Contrapulse, a brilliant study in polyrhythm and his first acknowledged work, was written in 1985, the year after he had moved to London to study with Oliver Knussen. It was followed one year later by Before Krishna, the first of Vir’s works to acknowledge his Indian background. Winner of the 1987 Benjamin Britten Composition Prize, it displays a refinement of sound and firm grasp of structure that have remained hallmarks of his music ever since.

Before Krishna marked a turning point for Vir. Having forged his own synthesis of modernist aesthetics and Indian mythology, he now felt confident enough to explore its potential in other directions. Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, written in 1988 for six singers of the London Sinfonietta Voices, used both polyrhythm and ancient Vedic chant to define the limits of an atmospheric setting of a poem by Rabindranath Tagore on the subject of creation. The poem’s translator, William Radice, was also librettist for Vir’s Tagore-based first opera, Snatched by the Gods, premiered in Amsterdam in 1992 as a double bill with his second, Broken Strings, based on a Buddhist legend to a libretto by playwright David Rudkin.

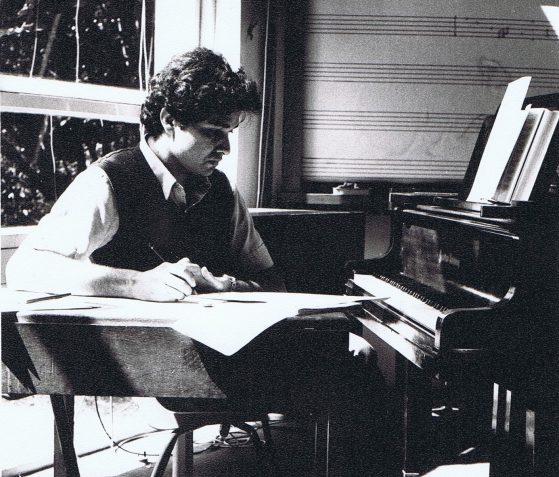

Param Vir composing at Dartington Summer School, July 1983, in the Masterclass of Peter Maxwell Davies

The music of these two stage-pieces, in its dramatic power and quality of invention at the service of the archetypal, often ritualistic theatre, signalled the debut of a major operatic composer for the 1990s and the new century. With them, too, emerged a new duality in Vir’s thinking in which micro- and macrocosm, soul and universe were seen as spiritually one. As Broken Strings, a play within a play, suggests, even music, most abstract of the arts, lives only through a harmony of opposites. Going further, Vir places the root of human suffering in our failure to perceive the need for integration. The tragic outcome of Snatched by the Gods arises precisely from our denial, as humans, of the cruelty in ourselves that we heap out so abundantly to others.

The polarities of male and female seen from a Tibetan Buddhist standpoint were the subject of Clear Light, Magic Body, written in 1993 for the virtuoso guitarist Jonathan Leathwood. With his first orchestral work, Horse Tooth White Rock, dedicated to Hans Werner Henze and conducted at its 1994 premiere by a longstanding supporter, Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Vir took the theme of Tibet to a wider audience. He made no secret of his belief that Chinese persecution of that country’s people and their culture was an evil as relevant to the well-being of the inner collective soul as to the outer health of the world community. In this two-movement tone poem on the subject of the saint Milarepa, Vir draws hope for the future from its journey from betrayal and revenge to transformation and spiritual vision. He has said that this kind of story, exploring the infinite possibilities of personal transformation, is the only kind that interests him. By implication, the path involves integration of the truth that lies within and without us, whether for saint, performer, listener or composer.

Revelation may arise when inner conflict is matched by outer tension, either personal or communal. This is a universal experience, unconfined to creed or culture. In 1996, in addition of Tender Light for viola da gamba and Gift for flute – works that celebrate friendship – Vir composed The Comfort of Angels for two pianos. The final movement of the latter takes a fragment of the Peacock’s Song from Broken Strings, where the bird sings of the sacredness of life, and develops the material in chorale form. Its original Buddhist context is transposed to that of a Western genre and sensibility.

Thus the power of love transcends the boundaries of culture and mythology, and does so again in Vir’s recent and perhaps most remarkable score, Ultimate words: Infinite song (1997). The courage and vision of Kim Malthe-Bruun, a young Danish Resistance fighter martyred by the Nazis, is celebrated in this song-cycle for baritone, piano and percussion sextet. The love, compassion and clear-headed wisdom overflowing from Kim’s final letters clearly acted as a powerful reagent on Vir’s imagination. Kim’s words are set as recitative and aria, while a taal, a rhythmic series typical of Indian music, is the basis of a fierce denunciation of evil in a central Drum Chant. Malthe-Bruun’s text inspired yet another work devoted to the theme of friendship: Flame (1997) for solo cello.

Since 1983, Vir in the course of his outstanding career has earned many prizes and other accolades, including the Benjamin Britten Composition Prize, the PRS Composition Prize, the Tippett Award and the Siemens Composition Prize (Munich). His work has been featured at international festivals such as Donaueschingen, Witten, Munich, and Berlin in Germany, England’s Aldeburgh and Almeida Opera Festivals and the Festival Musica Nova in Geneva. The real award, however, has been in the growth of a unique artistic vision and a language and technique, wholly the composer’s own, with which to express it. This has made possible works of the stature of Vir’s recent music. It promises many others, of no less depth and intensity, still to come.

Works featuring Indian Mythology

Biographical Essay by Nicholas Williams (1998)