ION

Opera in Two Acts

YEAR: 2000

YEAR OF REVISION: 2003

ORCHESTRATION: 1(pic,afl,bfl)1(ca)2(bcl:cbcl)1/2200/perc/hp.pf/str(1.1.1.1.1)

DURATION: 120'

LANGUAGE: English

LIBRETTO BY: David Lan, after Euripides

COMMISSIONED BY: Aldeburgh Festival and Almeida Opera

DEDICATION: Bill Casey

AVAILABILITY: Novello & Co. London

PREMIERE INFORMATION:

Almeida/Aldeburgh Opera, conducted by David Parry, with Stage Direction by Stephen Pimlott and Design by Alison Chitty. The presentation was semi-staged with Narrator, June 2000.

First Full Performance – Music Theatre Wales, in a co-production with Opéra National du Rhin and the Berliner Festwochen, with 19 performances from September to December 2003.

Conductor Michael Rafferty

Director Michael McCarthy

Designer Simon Banhams

Lighting Ace McCarron

INTRODUCTION:

“If ever an opera gazed into the psychological depths, it is surely this one…”

The Sunday Times

“immaculately crafted, with thoughtful vocal writing and vivid, arresting orchestration.”

The Telegraph

“Vir is not coy about writing “beautiful” music; there is some exquisitely lyrical writing.”

Opera

“…supremely lucid and musically appealing…”

The Independent

WORK NOTES:

Characters

Ion tenor

Creusa soprano

Xuthus, her husband bass

an Old Servant bass

a Servant baritone

Hermes, messenger of the gods baritone

the Pythia, a priestess of Apollo mezzo-soprano Athene, goddess of wisdom high soprano

Five Servants of Creusa 2 sopranos, 2 mezzo-sopranos, 1 contralto

TOWARDS ION

On the eve of its British premiere, Param Vir explains the gestation of his new opera Ion.

I was seventeen when I first read one of the Dialogues of Plato. I was thrilled by the vibrancy of its prose and for a time nurtured the idea of presenting the material (it was a dialogue on love) in theatrical form. This interest in Greek literature continued through my student years in Delhi, when I created music for productions of The Bacchae and Oedipus. Little inkling did I have then that 25 years later I would encounter Euripides’ Ion in a brilliant translation by David Lan, a version that convinced me that I had found my new opera.

European civilisation draws on a remarkable heritage from ancient Greece, a heritage rich in the arts and mythology. Its fabulous pantheon of gods and goddesses offers archetypes that help us to understand ourselves and interpret our experience. It is this quality of archetypes as well as the embodiment of ritual that gives Greek tragedy its unique and irresistible appeal. Euripides’ Ion is no exception, but, unusually for its time, it is not based on an oral epic. Its narrative is, rather, probably one of Euripides’ own invention, and dramatises the ancient Delphic injunction: ‘Know Yourself’. The light of self-knowledge irradiates the work in a steady stream of revelation, casts deep shadows, opens up caverns of despair. There is subtle allusion and irony and serious political issues lurk beneath the surface. Yet, at its heart, its finest truths are about love and love’s power to transform and heal.

Ion is a gift for a composer: its organic structure unfolds with a developmental energy that is symphonic in scope. It has, too, a unique intimacy, a depth of feeling, from which principal characters make moving statements. It places its narrative in a multi-dimensional world of gods, citizens and slaves, offers poignant development of character and pace through events that are unleashed with mythical fury. It takes pride in its sense of historical location in time and place. Like all great art, however, Ion effortlessly transcends its cultural identity to reach us in our modern world, surely as pristine and vibrant as when it was first received. Reading it as a composer, my initial impression was one of colour: feeling as colour, energy as colour, mood as colour, and it seemed to me suffused with light and sound. It presented a remarkable operatic opportunity.

I first saw the old Velacott translation of Ion and immediately realised that I had stumbled on a masterpiece. I was eager to encounter a modern rendition. I found this in David Lan’s version, which he had produced for the Royal Shakespeare Company. In its tender and delicate dialogues, I discovered the most searching exploration of love. For the opera David pared down and condensed the play, reshaping several speeches and choruses. The final libretto nevertheless remains true to the proportions and emotional pacing of the original.

In the first few months of my work on the opera, David and I consulted frequently, especially about my approach to the style of declamation. The exchange continued to the end; often it was a matter of us changing individual words or phrases to accommodate musical issues, or to adjust vocal lines to clarify the prosody. But this is quite usual in opera; it is precisely because it is such a collaborative idiom that I love opera as a musical form.

In creating the music that would reflect the work’s principal themes, my first concern was to define a harmonic language that might inflect and energise Euripides’ stratification of Greek society (gods, citizens, slaves) and determine how different characters embodied harmonic material. I also wanted to find a poignant and enduring symbol for the tender love that beats at the heart of the story, the love that joins Ion to Creusa, a son to his mother, and through her to Apollo. It had to be a symbol rooted in acoustic phenomena, aurally recognisable and not a mere abstraction.

I chose the simplest of means, by placing the interval of the perfect fifth at the centre: this first overtone after the octave would be the engine that would drive the harmony. Since much of the action of the drama seeks to connect Ion to his divine origins (he is Apollo’s son) and since the action of Apollo has such far-reaching consequences for the humans embroiled in the drama, the interval of the fifth permeates the music of all the principal characters. It is the principle leitmotiv amongst many. Chords based on stacked perfect fifths, the interval cycle of the 5th taken as a whole (the only cycle capable of going through 12 positions without repeating a pitch), other harmonies based on the fifth, whether in bursts of chords or melodic lines, symmetrical modes that affirm or deny the circle of fifths, these were the various means by which a multi-layered palette was created that could separate the worlds of gods, citizens and slaves, and yet find common threads running through them.

When I begin work on an opera, I often start with rough graphic drawings, an attempt to map each scene’s contours, texture and rhythmic quality in free-hand lines and colours. My impression of colour when I first read Ion was heightened when I encountered the sculptures of Anish Kapoor in 1998 as I began work. The raw energy-drawings eventually led to hundreds of rhythmic templates where the vocal line was paced against orchestral space in order to create a unified rhythmic-textural design. This allowed me to control the flow of text precisely and define the strands of counterpoint. There was also the problem of holding together long stretches of recitative in some unifying classical structure that would free the music from illustration. My solution was to impose taal cycles based on the conjunction of small rhythmic cells, taals that could underpin long recitatives and help characterise the declamation.

As regards orchestration, one strategy was to associate the principal characters with characteristic instrumental timbre; for example, Ion is often accompanied by solo cello, Creusa by solo viola and the Pythia by contrabass clarinet. Since string instruments are used to light up characters with the greatest degree of individuation, I avoided strings for the five Servants of Creusa; their accompaniment is primarily the ensemble of five woodwind instruments as in the opening scene, with successive choruses cumulatively enhanced by the addition of piano, percussion and brass.

When Ion was first presented in Aldeburgh and London in 2000, conductor David Parry and director Steven Pimlott devised a compelling presentation using a narrator to fill in sections that were not ready, in order to produce a complete theatrical experience. However I saw it as work in progress and there was never any question in my mind that the opera needed to find completion as originally designed. So the gaps were indeed plugged, but I also went back over other material and revised extensively.

Ion is dedicated to my friend Bill Casey for so many years of inspiration and friendship.

BRIEF SYNOPSIS

Ion is the story of a mother’s pain and grief, of a son lost and found and a timeless quest for truth, honesty and identity. Creusa, daughter of the King of Athens, searches for her abandoned son, the issue of an illicit liaison with Apollo. Accompanied by the women who are all too ready to rail against the injustices served upon their mistress, Creusa seeks guidance from the oracle, only to be cheated once again. Unwittingly she tries to kill the child she once left to die; in revenge, he attempts to kill her. Mother and son are eventually revealed to one another through an eleventh-hour intervention by Apollo’s priestess, the Pythia. The goddess Athene arrives, with her calming influence, to pacify the mortals, maintaining one further deception.

FULL SYNOPSIS

The opera takes place at Apollo’s shrine at Delphi.

Ion, the young caretaker of the shrine, greets Creusa the queen of Athens. Childless, she has come with her husband Xuthus to ask the oracle if she will ever give birth. She also has another motive. Years before she had been impregnated by the god Apollo. Terrified of the consequences, she abandoned the child. Now she believes that her infertility is a punishment for her heartlessness. Full of self-recrimination and anger with Apollo, she wants to know if there is any chance that her long lost son is still alive.

Publicly Ion denies that the god would ever behave so irresponsibly. In his heart he knows that this story is all too likely.

Xuthus enters the shrine and is informed that the first person he sees as he leaves will be his son. He chances to see Ion, claims him, and encourages him to return with him to Athens. After much persuasion, Ion accepts that what the oracle pronounces must be true. Xuthus arranges a feast to celebrate his joy.

Accompanied by her old Servant, Creusa learns that Xuthus has been given a child while she is to get nothing. She is overwhelmed by grief. The Servant spurs her to take revenge. Together they lay plans to kill Ion.

At the feast, by a happy chance Ion discovers that his celebratory cup of wine is poisoned. When tortured, the Servant admits that Creusa is the culprit. Ion threatens to kill her but, just in time, the Pythia who tends the oracle, reveals the basket in which Ion, when an infant, was brought to the temple. Creusa recognises it as her own. Ion is her long lost son.

The goddess Athene arrives and insists that Apollo was in no way trying to cover up his own misdeeds. He had given Ion to Xuthus for his own good, to make him heir to a royal house.

Accepting his good fortune and deeply moved to be reunited with his mother, Ion sets out for Athens.

(Synopsis by David Lan)

ION’s Aria

Act One, Scene One (Extract)

ION

Great Sun, with fingertips

you grasp high mountain peaks

and swing across the sky

bringing the day.

Myrrh and laurel

desert gathered

laid in clay jars

perfume the rafters.

Apollo’s priestess

perched beside

Apollo’s altar

croak the chant

Apollo whispers.

As for me, I do the tasks

I’ve carried out since childhood:

hang the walls with floral wreaths,

sweep doorways with laurel twigs.

From this jar I pour cool water

drawn from earth’s deep flowing fountains.

Only I with these pure hands,

purest of any temple servant,

may sanctify the temple courtyard.

Oh birds,

streaming down from Mount Parnassus,

don’t land here! Go away!

Doves! Swallows! Can’t you see

I’ve just swept here? Eagle,

You’ve made a pigsty of that pelmet.

Or you, fat Swan, get away! Shoo!

Divine Apollo admires your voice,

but that won’t save you. I’ll cut your throat.

I won’t.

The gods use birds as signs for mortals.

But dare pollute Apollo’s temple

I’ll bend my bow, I’ll aim my arrow . . .

(From the libretto by David Lan)

The Independent (30 October 2003)

Reviewer: Annette Morreau

Ion, Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, London

Param Vir’s supremely lucid and musically appealing Ion has been a long time in the making. After this summer’s dismal offerings of the Genesis Opera Project in collaboration with Aldeburgh Almeida Opera, here, at last, is a piece worthy of the description “opera”.

Ironically, Vir’s piece was commissioned by the same “backers”: in 2000, it received a concert performance at the Aldeburgh Festival. Now, London has just seen the UK premiere of the fully-fledged staged work – but nine performances had already taken place, a result of co-production with Opéra National du Rhin in Strasbourg and Berlin Festival, plus performances in Mulhouse and Colmar.

The fluency of the performance was palpable, even if European touring has meant three different orchestras. The indefatigable Michael Rafferty – music director of the astonishingly versatile Music Theatre Wales responsible for this show – seems seamlessly to have moved from one band to another. Euripides’ Ion makes a great operatic book. Vir came across it in translation by David Lan – known for his prize-winning TV drama documentaries and work with the RSC – and it was with him that he worked on clarifying the text and adapting it to musical form.

Ion is a myth for our times, although messing with Greek gods invariably produces twists: a barren couple, Creusa and Xuthus, seek advice from Apollo individually, only for Xuthus to be told that the first person he sees will be his son. The wife feels thwarted – wasn’t it really her shame? – so she vows to kill the “imposed” son. But then she has a secret: she was a single mother impregnated by none other than Apollo and thought that she had left the child out to die. But the child did not die, rather it became the caretaker of Apollo’s Delphic shrine – none other than Ion, the first person Xuthus encounters.

Creusa’s plot to poison Ion goes wrong – the wine, instead of being drunk, is thrown on the ground for a hapless dove to take a nip and expire – so Creusa, herself, is condemned to die. But the Pythia, a matronly figure who tends the oracle, reveals that in her possession is a basket in which she found a child. Recognition and joy all round.

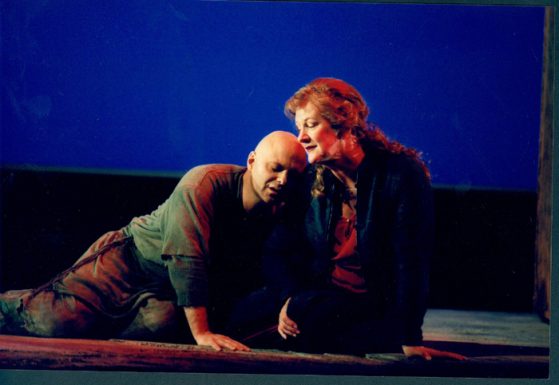

Michael Bennett was a touching Ion, if occasionally pressing the voice too hard; Rita Cullis and Graeme Danby a believable middle-aged couple; Gwion Thomas a supremely musical Hermes (and Servant); Nuala Willis sonorous as the Pythia; and Louise Walsh, the (somewhat unlikely) coloratura Athene. Michael McCarthy’s production was affecting and stately, Ace McCarron magically lighting Simon Banham’s design. A triumph.

The Sunday Times (18 June 2000)

If ever an opera gazed into the psychological depths, it is surely this one…